Up at 7.30. It has been the same everyday. People stir and poke their heads out of their curtained bunks or sit on the edge looking a bit dazed. These people who were strangers 10 days ago now familiar. A team. A crew.

It’s overcast and still. A sea otter is in a bay a few hundred metres away. You can see his head pop out of the water, bob around a bit and then his sleak back arches as he dives. The last thing to disappear are his pad shaped feet. We see him come up several times and calmly paddle, just his head visible. Suddenly the glass of the surface is shattered by tiny fish scattering. Calm on the surface but clearly active beneath.

Trying to sail but it doesn’t seem to work. Skipper is yelling and rushing to get the sails up. Several of us wonder what the rush is.

1st mate ‘Calm down’

‘I can’t!’

It reminds me of a comedy sketch but can’t remember which one.

Once again we get all the sails up for less than 30 minutes. I seem to be the bow sprit boy now. Three times now I have had to climb up the bow sprit to fold or unfold the the jibs.

It’s precarious. There’s a clutter of ropes, sails and wires. I climb over the bow onto the ratlins, the ropes that connect to the bow sprit meant for walking on not looking at the water beneath my feet or even worse imagining what would happen if I fall in and get mown down by a 100 foot ketch.

I have to straddle the bow sprit along with Taylor and Richard and reach over and start folding the sails into their creases before wrapping them up into a sausage and then tie them to the sprit with the Gaskells (ropes).

Once we’ve done one it’s onto the next two. The final one at the end the ratlins runout and Taylor and I are sitting only on the whiskers, the bendy bouncy wires that run along the outside of the sprit. My legs are more hesitant each time I take a step. There’s a whisker to sit on and a whisker to stand on while you pull and fold and push and wrap.

Yet it’s incredibly exhilarating. A mixture of adrenaline, workmanship, teamwork and the realisation that we’re in the middle of nowhere holding onto the very tip of an old boat makes me smile and then laugh.

‘Come on James we haven’t got time to look at the view. Get back on board!’ It’s like being back at school.

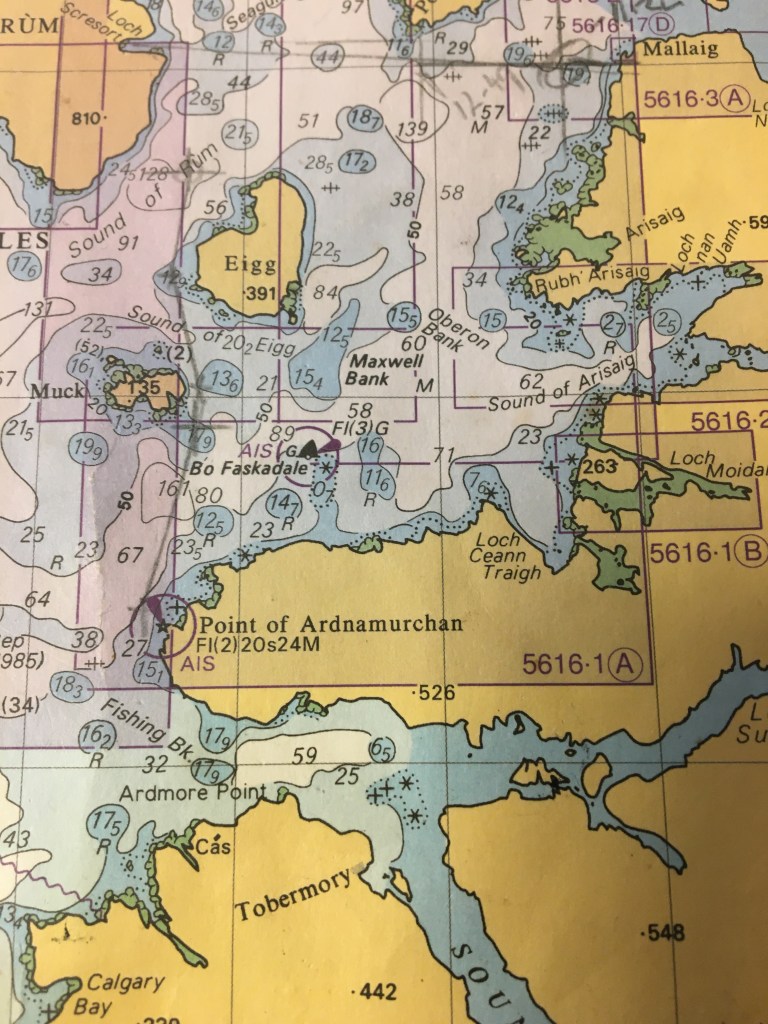

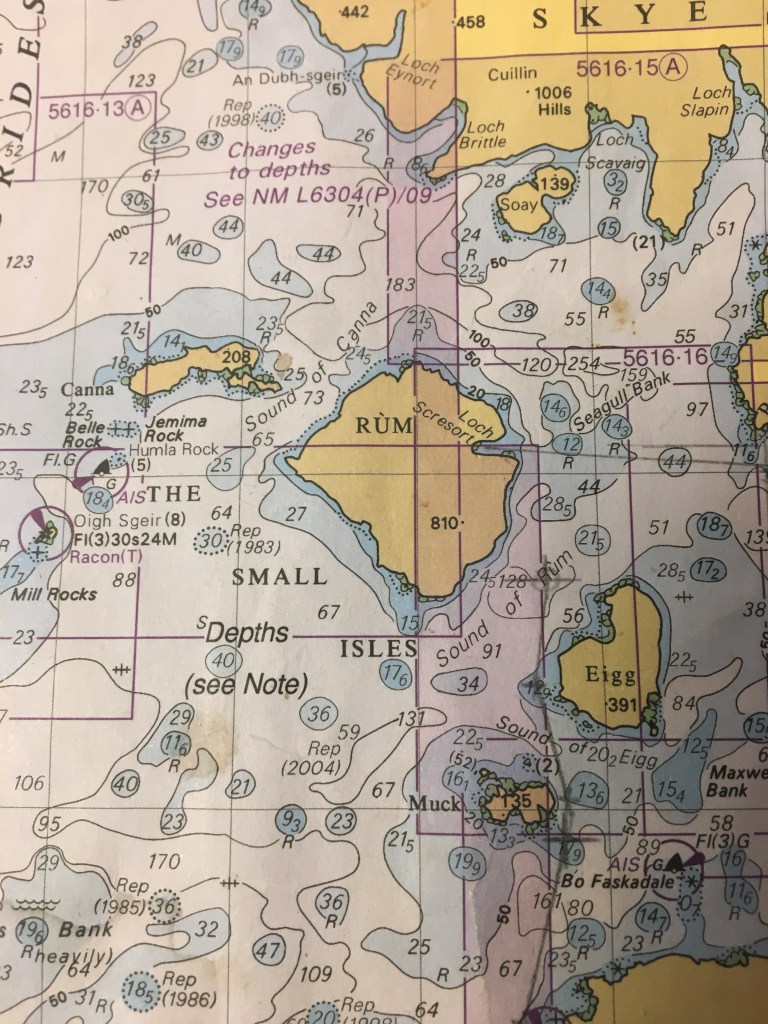

We get back into the Sound of Mull. Looking out for buoys. The sun comes out after lunch and we motor. We have sails up but it makes little difference. Under sail we make about a knot.

We are heading for the Isle of Kerrera for our last night. It is just off Oban so that we can get back to port in time for our disembark time of 10 am on Monday.

We have to tack a few times to get round the corner of Kerrera. As we come into the bay on the western edge is a lighthouse repair vessel, the Pharos.

Once again we’re in the rib to go to Gylen Castle, a narrow ruined Castle which stands on a promontory looking to the eastern coast of Mull. It is like something out of a picture book or film.

After it was built it was owned by the MacDougalls but was only lived in for 65 years (by a garrison) before it was put under siege, the men were forced to surrender with the promise of imprisonment before they were all slaughtered.

Everywhere here there are remnants of a brutal and savage past where massacre and slaughter seemed to be regular occurrences.

Swam off the rocks in the clearest blue sea. Used to the cold now. Always the fear going in. It disappears as soon as I’m in.

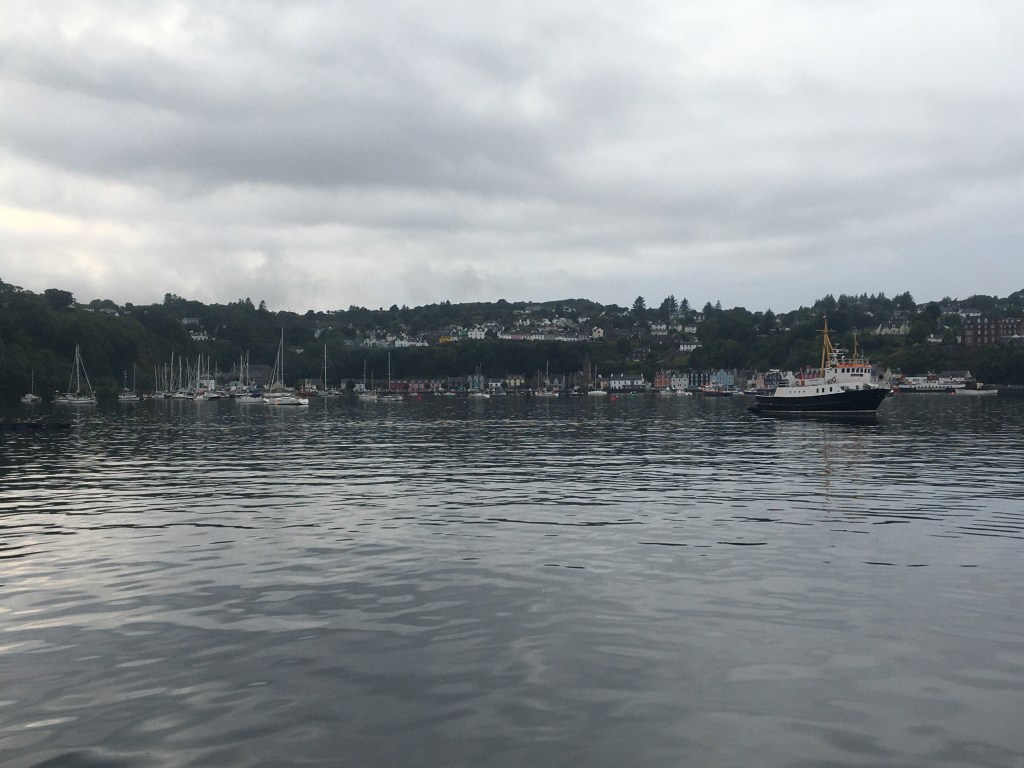

It’s an hour’s walk to the eastern side of Kerrera to meet the Bessie Ellen. As always she stands out as she has in every destination I’ve seen her.

I am on the jetty waving to get the rib to pick me up for the last time.

Back on deck we have drinks and look at the promenade of Oban. Tomorrow it takes only 30 minutes to get there. We’ll say goodbye and part, most of us never to see each other again but just for a few days we shared adventures, experiences, stories, skills and knowledge. It’s been intense and full of wonder. I’m already planning a greater adventure for next year.